When Russia took over parts of Ukraine in 2014, leading to what in 2022 would become the first full-scale war in Europe since WWII, Russia’s government-controlled media claimed that the rationale for the war was the safekeeping of the so-called “russkii mir”—the Russian World. As presented by Russian state propaganda, the Russian World evokes an unsettling resemblance to Hitlerite ideology, constructing an image of a superior and sacred geographic, historic, cultural, and linguistic space; it also propagates the preservation of conservative values that contrast the perceived moral corruption of the modern Western Civilization.

In a counterstrike, Russian and Russophone poets of Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Israel, USA, Canada, Germany, and other countries immediately began recording their horror and outrage at the war and making their records public via social networks, blogs, and performances. In early 2022, the poet and scholar Julia Nemirovskaya founded the Kopilka Project. The original mandate for the Kopilka, or The Coin-Bank, was to collect and preserve the work of poets in Russia who faced the threat of persecution and incarceration for speaking out against the so-called “special military operation” in Ukraine. Soon, the Kopilka expanded to include the work of Russophone poets everywhere in the world.

As the war dragged on and the antiwar poetic output grew, the Kopilka grew as well. It gained more voices, perspectives, texts, and tongues. Translators into English, German, French, Hungarian, and other languages volunteered to work on the poems that spoke to them and to place their translations in magazines and collections. Thus, solo literary pickets staged by poet protesters turned into an antiwar poetry rally; diverse and idiosyncratic poetic voices were joined in a dramatic choir. Like the masked chanters of a Greek chorus, Kopilka poets formulate the moral issues of the war and offer commentary on death and suffering in a much needed language of witness—a language many believed impossible to conjure after the first shock of the war struck them mute.

Over the past year-and-a-half, Kopilka has served as a source for two anthologies of antiwar poetry: Non à la Guerre! in French (Characteres) and Disbelief: 100 Anti-War Poems in English and Russian (Smokestack Books). Dislocation is the third and the largest Kopilka anthology to date. It reflects both the torrents of civic poetry written during the years of the war and the new shifts in the course of the war and in the lives of the poets who write about it.

Between February 2022 and now, early hopes for a quick resolution waned and international calls for peace were supplanted by calls for victory for Ukraine; Ukraine’s economic infrastructure was decimated by Russian airstrikes; millions of people fled or were displaced; casualties numbered in tens of thousands; Russia’s jingoistic public discourse, draconian legislature, and brutal law-enforcement tactics gathered ever more momentum; the fear of a nuclear conflict reached a Cold War–level high. Under these realities, many poets have abandoned their usual peacetime themes and now write exclusively civic poetry. Ongoing atrocities in Ukraine and grim political changes in Russia keep calling for insistent poetic attention, reflection, and protest—and so poets keep writing. Many poets who lived in Russia at the beginning of the war relocated to other countries—and they keep writing from the place of their displacement as they grapple with new surroundings. Several poets in Russia have been dragged through courts or jailed for writing about the war—and they keep writing.

Dislocation offers a sampling of striking, memorable poetry within a wide thematic and stylistic range. In their distinct authorial voices, poets write of warnings, omens, and premonitions; of fear, fury, and grief; of pain, alienation and separation; of injury, death, and mourning; of loss of hope—and of hope against hope. The title of this collection evokes literal and metaphoric dislocations: lives fractured, habitats destroyed, affiliations severed, expectations misplaced, destinies smashed and haphazardly glued back together.

The poetry in Dislocation is organized into twelve concept clusters evolving around pain, rage, guilt; juxtapositions of the atrocities with the sacral and the meaning of life; dramas of nationhood, strategies of resistance and (im-)possibilities of recovery. The clusters offer the reader the opportunity to see common themes synthetically emerge in the independent works.

The anthology is a large translation project. The overarching goal of the group of translators, which includes Maria Bloshteyn, Andrei Burago, Richard Coombes, Yana Kane, Anna Krushelnitskaya, Dmitri Manin, and Josephine von Zitzewitz, was to represent the voices of the poets, offer them a reach into a new linguistic space, and open a window into the poets’ worlds for the English-speaking reader. Meeting this task requires giving equal priority to the “what” and the “how” of a poetic utterance, since the message, the tone, the vocabulary, the form, and the expressive devices are equally important in rendering the poetic voice. The translators were like-minded in their effort to create translations which work as poems in their own right in English while being faithful to the originals, and to represent the distinguishing features of each author’s style consistently even when different translators work on the same poet. Many translations were collectively discussed and workshopped.

The work of certain poets appears in the anthology under initials or nom-deplumes because those authors risk losing their freedom for writing antiwar messages—but the translators made sure no author’s voice is anonymized, and the distinctiveness of the poems is never overlooked in translation.

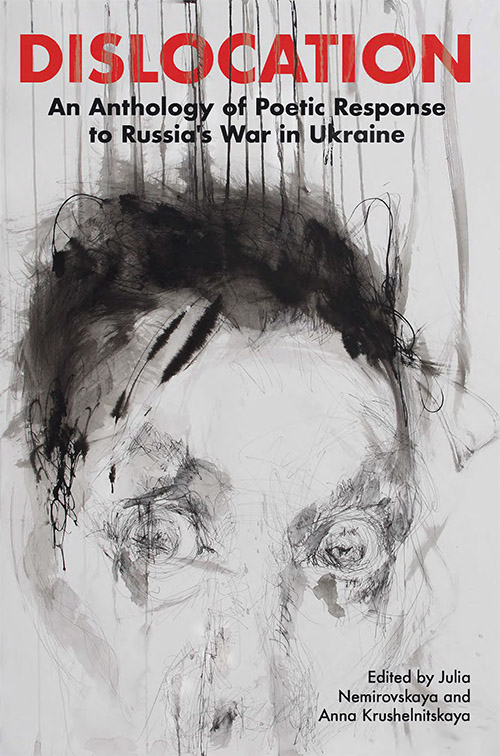

The anthology’s theme is visually complemented by striking cover art created by the artist Maria Kazanskaya. Each chapter of the anthology is preceded by evocative photographs by the poet and photographer Andrei Grishaev. Short bios of the poets of the anthology—save for the bios of those authors who did not feel safe disclosing identifying information—are included at the end of the book.

Editors